-40%

1876 Centennial World Fair Colorado Original Hayden Survey Display WH Holmes

$ 1848

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

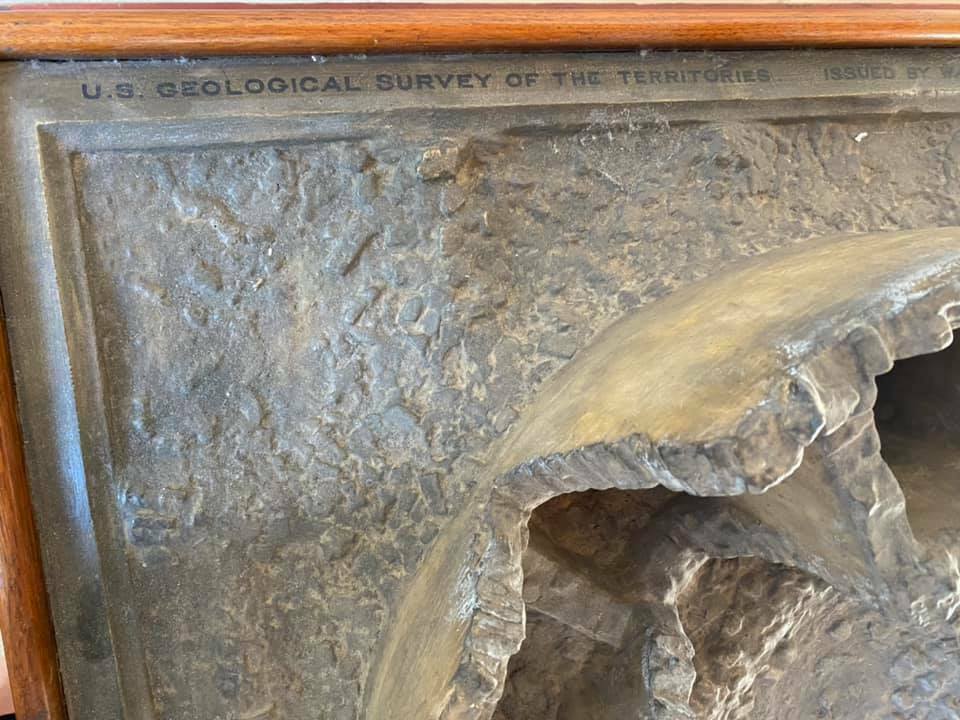

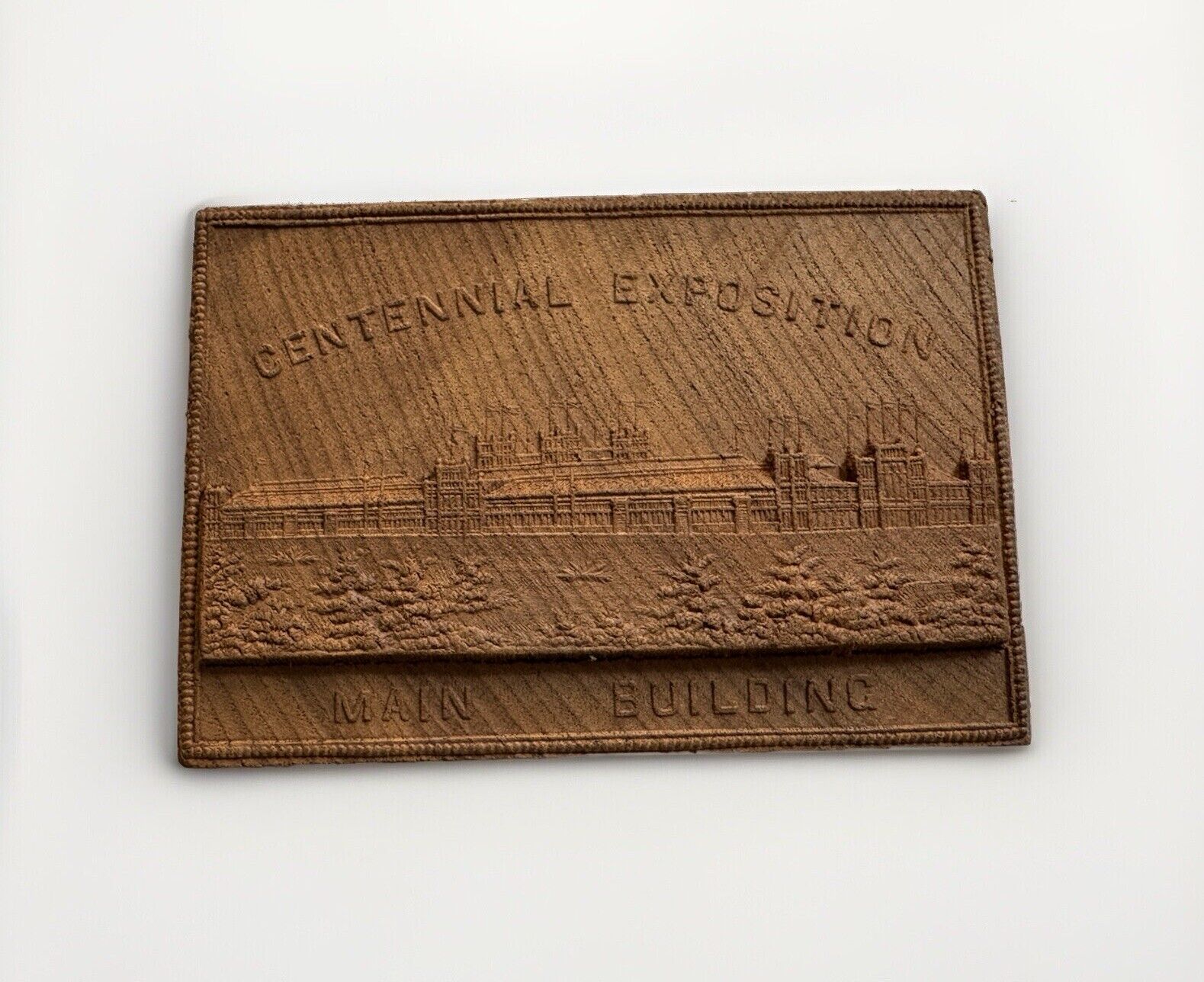

An original display model from the 1876 Centennial Exposition (First World Fair in the US) of a prehistoric ruin (Three Walled Tower) in Southwest Colorado by William Henry Holmes. This amazing piece by Holmes lies intact nearly 144 years later and represents the rich legacy of the Hayden survey which explored Yellowstone National Park, Montana, Colorado, and parts of Northern Arizona. In addition, this piece represents the origins of the Smithsonian, since the government display at the 1876 Centennial was organized by the US government and later led to the building of the Smithsonian in Washington DC. For those that are interested in a more in depth history, we recommend looking up the biographies of William Henry Jackson, William Henry Holmes, Ferdinand Hayden, and the Smithsonian. This is a one of kind piece and are happy to answer any questions that you may have! Thanks for being interested in history!Dimensions: 30 x 30 inches (Display Table Is Included)

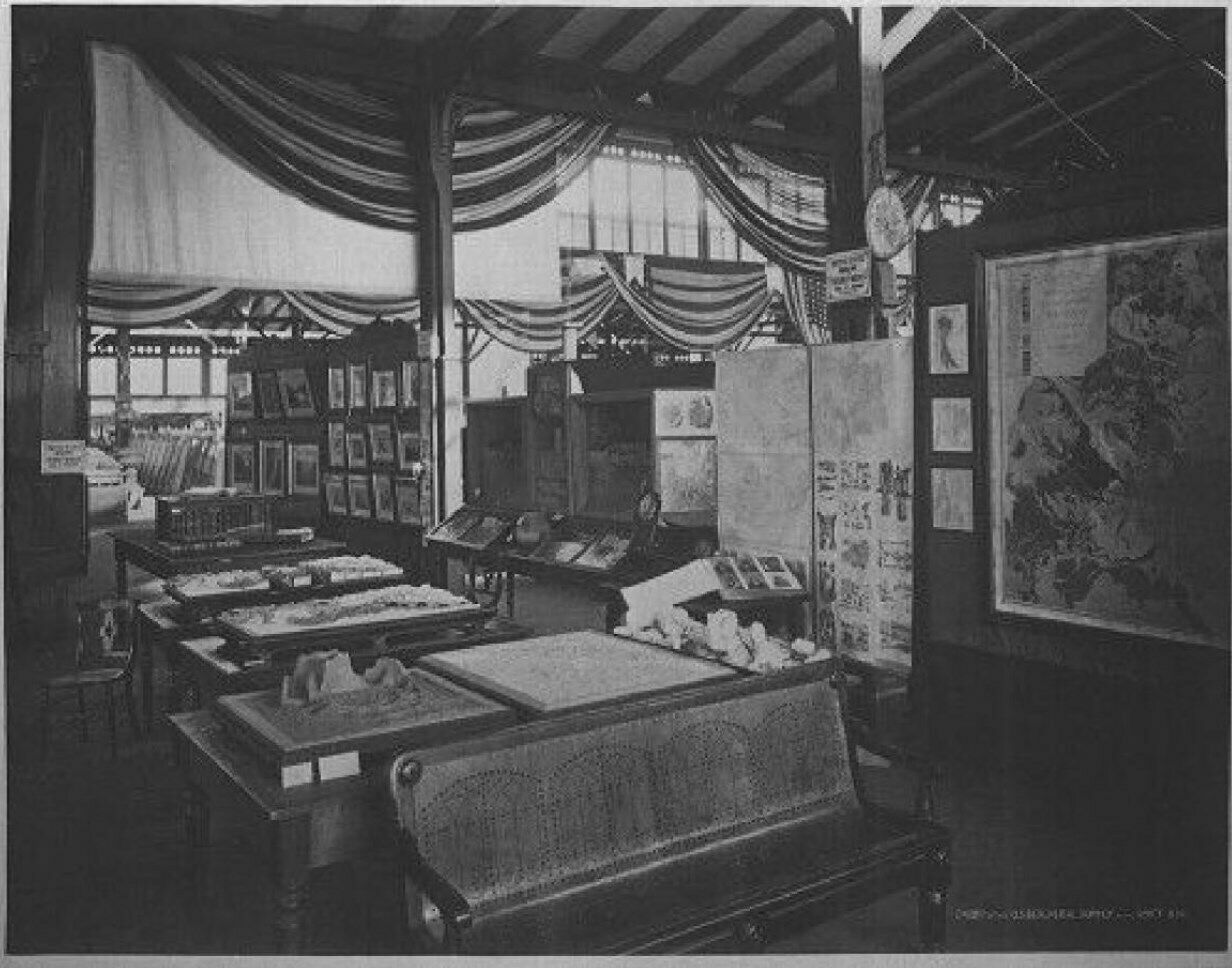

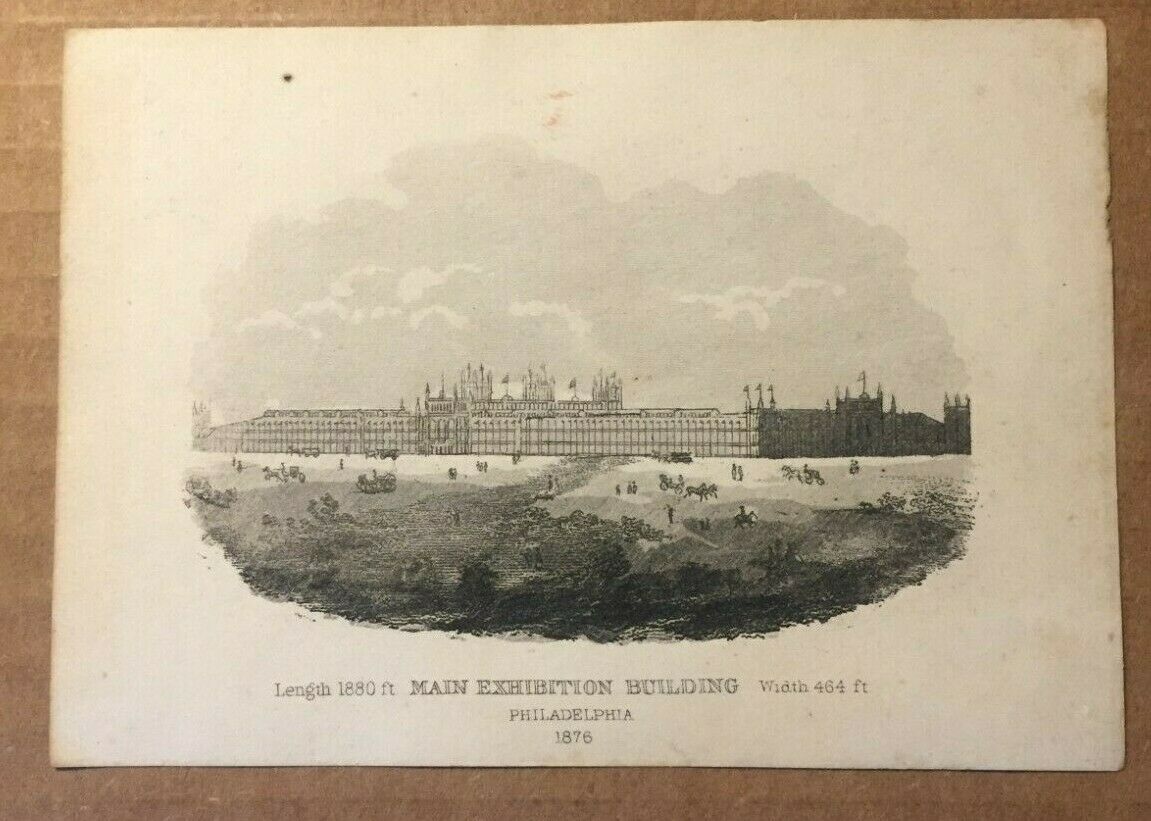

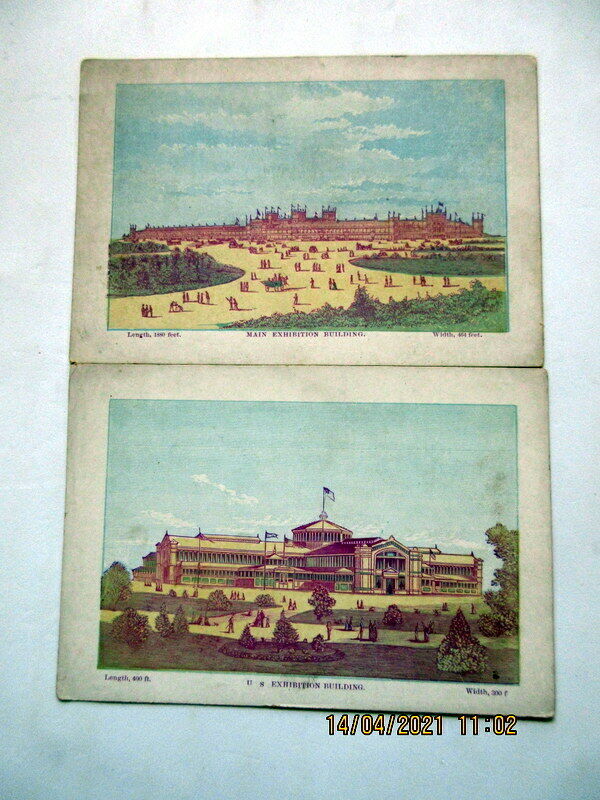

Description of 1876 Centennial Exposition (William Henry Jackson and William Henry Holmes, Hayden Survey USGS Exhibit, Government Building, Philadelphia

“The occasion of the display at the International Exhibition at Philadelphia led to a desire to represent as forcibly as possible some of the recent discoveries of the Survey of remarkable ancient ruins in Southwestern Colorado, and the success of Mr. Holmes with the Elk Mountain models suggested the same means for effecting this purpose. That are six no completed of archaeological subjects, as follows:-

The Mancos Cliff House, by Mr. Holmes, represents a ruin in an exceeding well preserved condition, perched upon a little shelf, or niche, in the face of a bluff, 800 feet vertically above the valley below. The model is 30 by 40 inches in dimensions, and the scale four feet to one inch.

An ancient Cave Town in the lower canyon of the De Chelly, near the San Juan River, represents a very interesting and extensive ruin, built along a narrow shelf, or bench, seventy five feet above the valley, and overhung by the bluff. The whole ruin is nearly six hundred feet in length, with originally about one hundred or more apartments. The model as constructed by Mr. W.H. Jackson is forty inches in length, and show’s one third of the ruin, the scale is six feet to one inch.

A restoration of the above, also by Mr. Jackson, is the subject of the the third of the series. In this, buildings are built up to the condition in which they were originally supposed to have been before their desertion. They show many points of resemblance to the present Moquis in Northwestern Arizona, noticeably so in the use of the ladder to reach their houses. Groups of miniature people have been arranged about the model, representing them engaged in various occupations, with their pottery and other domestic utensils.

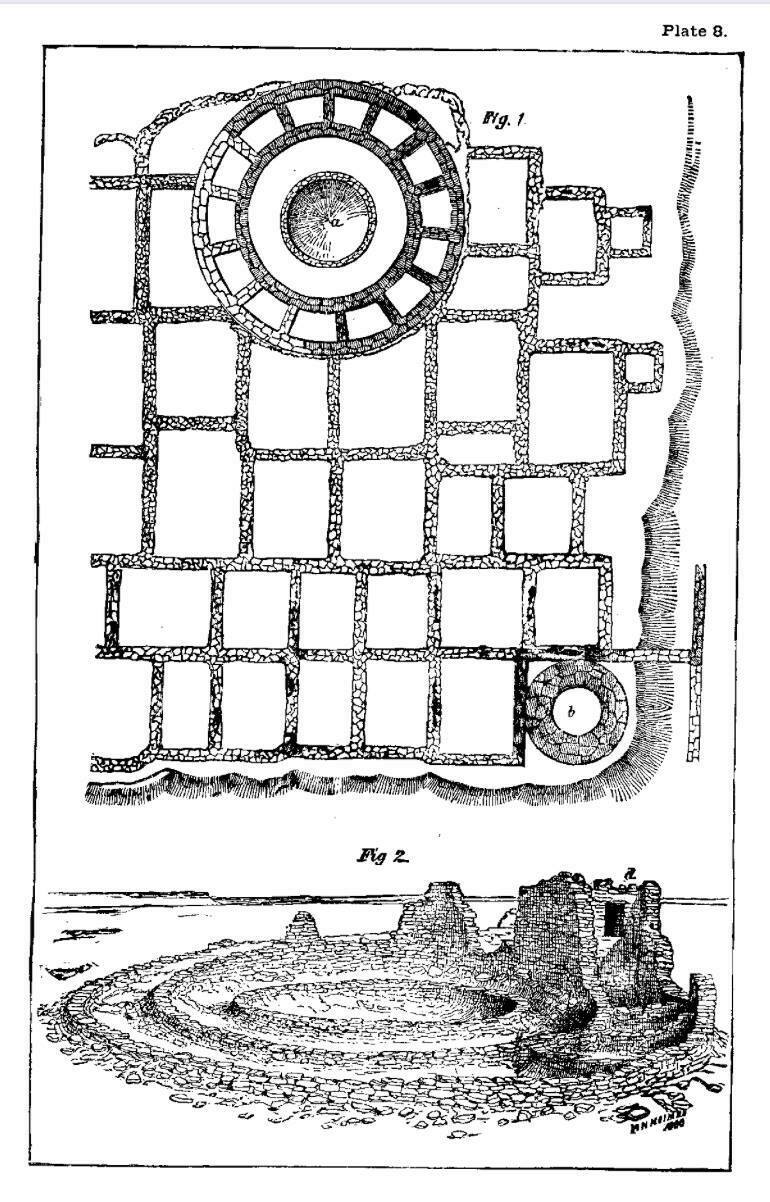

The Great Triple Walled Tower, on the McElmo, by Mr. Holmes, is a horizontal model thirty inches square, representing, on a scale of two feet to one inch, the ruins of an exceedingly interesting circular stone tower in Southwestern Colorado.

The fifth in the series is a model of a Cliff House, in the bluff of the lower canon of the Rio De Chelly in Arizona, on a scale of three feet to one inch, and in the same size as the Mancos model. This is especially intended to show the manner in which its former occupants passed up and down the steep face of the bluff in which it is built, by steps hewn into the rock.

The two models were meant to represent the present and the past, the site as it now appeared and a reconstructed version of its original condition. The underlying message implied by these models was the continuity of ancient primitive ruins linking past and present, conforming what Curtis Hensley has pointed out in the use of such Indian sites conveying a sense of national identity and historical lineage after the Civil War.

Description of William Henry Holmes’ involvement in the 1876 Centennial

"For the next several years Jackson continued his photographic journeys, discovering and documenting numerous ruins of cliff dwellings and countryside. In 1876 he Hayden assigned Jackson to organize the Surveys’ exhibition at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia."

Ferdinand Hayden’s Survey display at the 1876 Centennial included framed photographs (back wall, right) relief maps, models of the Yellowstone National Park, and the state of Colorado (center tables), and two shadow box models of recent discovered Indian cliff houses (center right). The opened album of Indian portraits (center, right) contained some of the extensive collection made by William Henry Jackson and other photographers for Hayden’s Survey photographic collection. (William Henry Jackson, “Display of the US Geological Survey in the Government Building, 1876, albumen, 42.8 x 55.7cm, Photography Collection, George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film, Rochester

Description of The Geographical Survey Of The Territories

The United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories was established by an act of Congress on 2 March 1867 as an agency under the Department of the Interior (later the General Land Office) tasked to complete a geographical survey of the State of Nebraska which had been admitted to the Union the day before. The scope of the survey eventual grew to include all the American territories adjacent to the Rocky Mountains encompassing hundreds of thousands of square miles. The survey over its existence was headed by Dr. Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden who published a number of reports between 1867 and 1883 on the region’s geography, geology, topography, ethnology, philology, paleontology and other allied subjects. Congress originally appropriated ,000 in 1867 for the survey of Nebraska and a similar amount the following year to survey the Wyoming Territory. As the survey’s workload increased over its existence, so did its budget and by the end of its tenure in early 1880s, Congress had appropriated approximately 0,000 for the surveys of the West, a figure that did not include some clerical and printing expenditures."

William Henry Holmes and Richard Wetherill (Mesa Verde)

Holmes was an assistant geologist on the Hayden Survey, which was one of several scientific expeditions that were sent out by the federal government to document the geologic resources of the United States. He was also “assigned the very agreeable task of making examinations of such ancient remains as might be included in the district surveyed.” He considered part of his duty to collect items of interest for contribution to the National Museum in Washington, D. C.

William Henry Holmes made this drawing of some of the pottery he found

The leader of the expedition, F. V. Hayden, listed the types of materials Holmes removed: “A good collection of pottery, stone implements, the latter including arrow-heads, axes, and ear-ornaments, etc., some pieces of rope, fragments of matting, water-jars, corn, and beans, and other articles were exhumed from the

débris

of a house. Many graves were found, and a number of skulls and skeletons that may fairly be attributed to the prehistoric inhabitants were added to the collection.”

Washington, D. C. had no shortage of artifacts, funerary goods, and human remains on museum storage shelves. In 1861, the Smithsonian Institution had issued a bulletin entitled “Instructions for Archaeological Investigations in the U. States,” which appealed for the collection of such materials.

“

The Smithsonian Institution, being desirous of adding to its collections in archaeology all such material as bears upon the physical type, the arts and manufactures of the original inhabitants of America, solicits the co-operation of officers of the army and navy, missionaries, superintendents, and agents of the Indian department, residents in the Indian country, and travelers to that end.

“

Among the first of these desiderata is a full series of the skulls of American Indians….

“

Another department to which the Institution wishes to direct the attention of collectors is that of the weapons, implements, and utensils, the various manufactures, ornaments, dresses, &c., of the Indian tribes.

“

Archaeological loot, such as the items Holmes collected, arrived in great quantities in Washington. By the late twentieth century, when they finally came to realize that they were wrong to possess human remains, the Smithsonian had a virtual cemetery in their storage cabinets including corpses and body parts of some 18,500 Native American individuals.

During his 1875 explorations, Holmes had several encounters with Native Americans—Utes, Paiutes, and Navajos. He called them “fierce looking devils,” “thieving pirates,” “cowardly scamps,” and “a herd of meddlesome and treacherous savages.” He wrote that “these fellows came more nearly up to my notion of what fiends of hell ought to be than any mortals I have seen.” It is ironic that he later served in the U. S. Bureau of Ethnology in a role that was, at least superficially, respectful of Natives.

Holmes predicted that “a rich reward awaits the fortunate archaeologist who shall be able to thoroughly investigate the historical records that lie buried in the masses of ruins, the unexplored caves, and the still mysterious burial places of the Southwest.” However, despite widespread publicity by Holmes and others, it would be several decades before any American scientist took an interest in the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings."